According to a study, mothers of chronically unwell children seek out more health treatments

Researchers from Stanford University and Aarhus University in Denmark discovered that mothers of chronically ill children use health care services more frequently, particularly psychotherapy, to help them cope with the daily demands of parenting.

Caring for a chronically unwell child has an influence that goes beyond the mothers’ daily struggles. “We’re only witnessing the tip of the iceberg,” said Kyung Mi Kim, Ph.D., a Stanford Clinical Excellence Research Center research fellow. The study, which was published in December in PLOS ONE, was co-authored by her and Nirav Shah, MD, a senior scholar at the institute.

“The long-term physical and psychological demands of caregiving take a toll on caregiving mothers’ health and can compel them to leave the workforce,” Kim added.

Senior writers included CERC director Arnold Milstein, University of Toronto associated scholar Eyal Cohen, MD, and CERC senior adviser Henrik Toft Srensen, MD, Ph.D., of Denmark’s Aarhus University.

According to the researchers, a deeper knowledge of the obstacles experienced by moms of chronically unwell children will lead to interventions that preserve their physical and mental health.

Longer paid maternity leave to promote mothers’ postpartum recovery and paid child care leave when the caring burden is significant are two examples. As many as 2% to 3% of all kids born in the United States each year have congenital malformations, such as Down syndrome and heart disorders, such procedures potentially benefit a substantial number of moms.

Data from Denmark

Due to a lack of longitudinal data, research on the use of health care services by mothers of chronically ill children has been limited. The researchers decided to Denmark for this study because it is one of the only countries that uses its national birth and medical registers to track health-care usage over decades.

Because Denmark’s national health care system covers all primary, specialist, inpatient, and mental health services, researchers were able to look at the long-term effects of caregiver burden without taking into account whether participants had access to care or the ability to pay for services, both of which are factors in the United States’ health care system.

Between 1997 and 2017, 23,927 Danish mothers gave birth to infants with serious congenital abnormalities, alongside a control group of moms of unaffected infants. The births were documented in Denmark’s medical birth registry.

Major congenital anomalies are structural or functional abnormalities that occur at birth and have a significant influence on health and functioning.

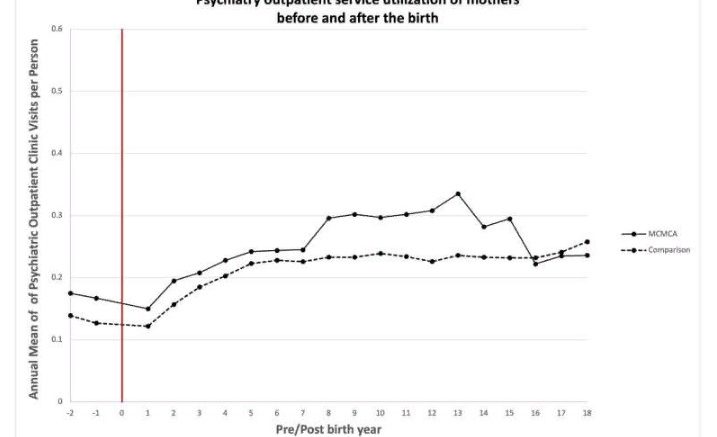

The researchers discovered that moms of chronically unwell children under the age of six utilized inpatient services 39 percent more than other mothers, and mothers of chronically ill children aged seven to thirteen used inpatient services 14 percent more.

Mothers of impacted children from seven to thirteen years old used mental health services the most: These moms needed 22% more mental health services than mothers of unaffected children, and the number was significantly greater for low-income women, who required 59 percent more psychotherapy when their children were seven to thirteen years old.

Increased utilization of health care results in a considerable cost increase: Denmark’s per capita health-care spending was $5,568 in 2019, implying that a 1% increase in health-care consumption would result in a $325 million annual increase for the country of 5.8 million people. When applied to the United States, a similar increase in health-care utilization would have an even higher impact, given that the United States spends twice as much per capita on health-care than Denmark.

A glance at the job market

The study published in PLOS ONE is the first of three by researchers at the institute looking into the effects of caring on mothers.

A report due out this summer will look at the impact on mothers’ work, which has been a recurring subject during the COVID-19 pandemic, since the duty of caring for family members has rested disproportionately on women, compelling many to leave their careers. A third research will look at how moms caring for chronically ill children affect society as a whole.

“It’s vital to develop care plans that provide long-term support while also reducing financial and time pressures,” Kim added. “This will have far-reaching health and labor-force repercussions in the long run.”