Jackie Robinson’s legacy of success Why can’t successes and championships do the same for Black managers as Robinson’s achievements did for baseball’s color barrier?

For the past ten years, April 15 has been my day to honor Jackie Robinson.

On this day in 1947, Robinson made his major league sports debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, breaking the color barrier that had previously kept black players out of baseball.

This is the day when baseball players all across the world will wear Robinson’s No. 42, and baseball owners and executives will pay tribute to a pioneering black man who died nearly 50 years ago.

On this day, opponents will remind us that the issues Robinson fought against, particularly the absence of black managers and executives, persist.

“I am quite delighted and pleased to be here this afternoon,” Robinson remarked during the World Series in 1972, “but I must admit that I am going to be even more pleased and proud when I look at the third base coaching line one day and see a black face managing in baseball.”

Robinson succumbed to his injuries nine days later.

Only two black managers remain now, Dave Roberts of the Los Angeles Dodgers and the venerable Dusty Baker of the Houston Astros, nearly five decades after his death.

We’ve been debating this for decades, not only in baseball but also in professional football and, to a lesser extent, professional basketball.

I’ve been attempting to come up with a strategy other than appealing to the owners’ sense of fairness to overcome white men’s aversion to appointing black men to lead their sports teams.

Perhaps we need to win more, I reasoned. Perhaps we require the services of a superstar black head coach and general manager.

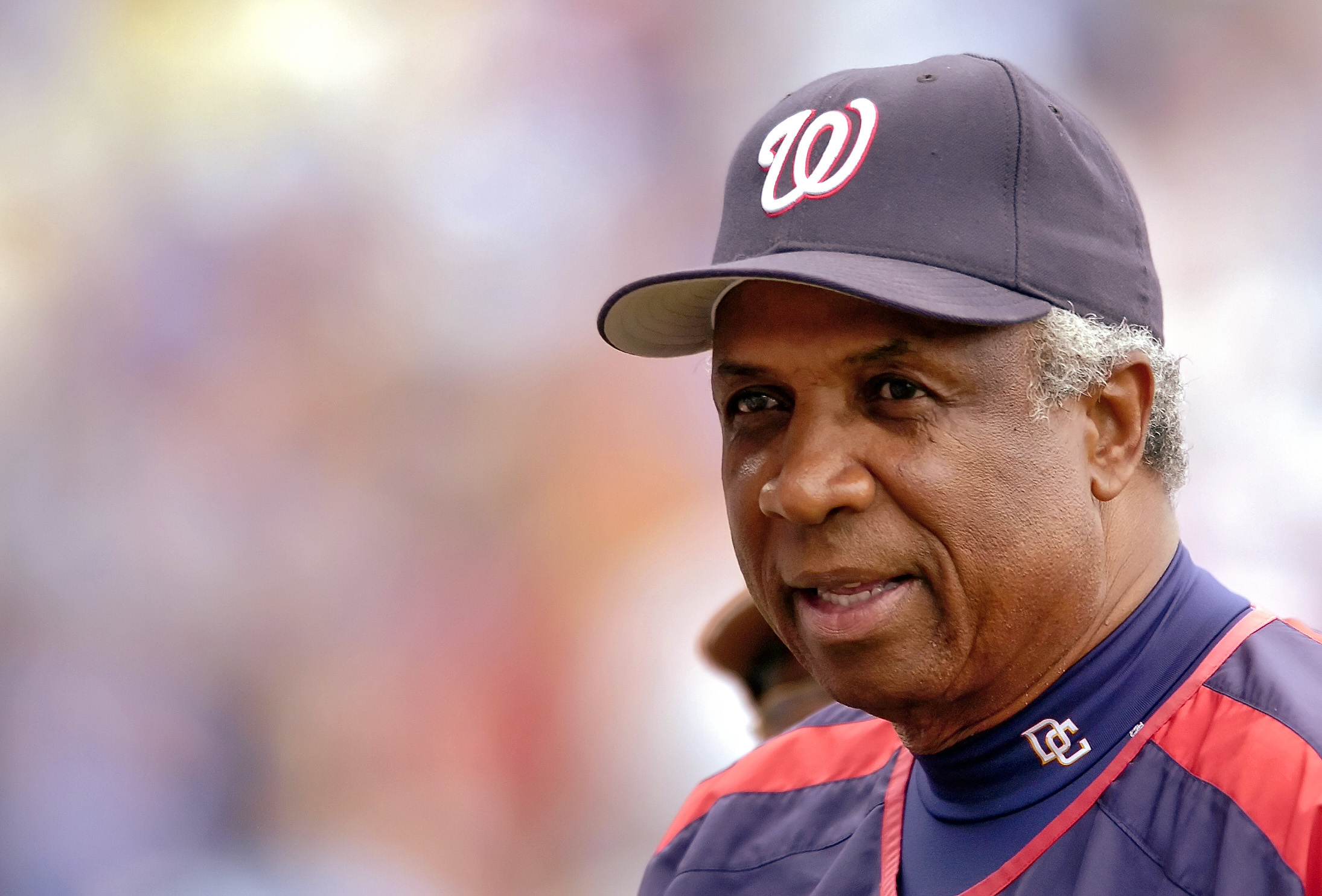

Frank Robinson, pictured in 2006 as manager of the Washington Nationals, was MLB’s first Black manager in 1975

Because of his talent, Robinson is credited with opening doors for future generations of black players. Would a superstar black baseball manager or a superstar black football head coach open doors for future generations of black head coaches and managers?

What exactly do I mean when I say “superstar”? I’m talking about Bill Belichick, who has won multiple Super Bowls, and Joe Torre, who has won multiple World Series championships.

I realize that asking the question could be interpreted as blaming the victim. I could be accused of arguing that systemic racism isn’t a barrier to black managers and coaches getting ahead. The obstacles are that they haven’t won big enough and frequently enough.

However, there are a slew of reasons why this hasn’t happened.

This week, Hall of Fame sportswriter Claire Smith reminded me that black baseball managers are frequently assigned to bad teams.

“One of the biggest challenges for almost every manager of color has been being brought in to manage teams that aren’t quite playoff-ready,” she explained. “So it’s difficult to get there and even harder to win those championships.”

According to Smith, Torre was given a good Yankees team to begin with, and he was given more and more resources until he led the Yankees to four World Series championships.

In his 16 years as the manager of four franchises, Frank Robinson, who became baseball’s first black manager in 1975, was always building and only had five winning seasons. Don Baylor was always building in Colorado and Chicago, and the two teams combined for four winning seasons in nine years.

On the plus side, Roberts has three World Series rings and has won a championship with the Dodgers. Baker was the manager of the San Francisco Giants when they won the World Series in 2002.

In 2003, he was one win away from leading the Chicago Cubs to the World Series. He’s managed the Cincinnati Reds, Washington Nationals, and now the Houston Astros, whom he led to the World Series last year. Baker is on pace to win his 2,000th game as a manager by May, making him the first black manager to do so.

“There have been additional challenges for African American managers, such as not always remaining in the candidate pool, whereas you’ll see managers with losing records,” Smith said.

As I considered more superstar managers and coaches, I came up with a name that makes a strong case against my claim that winning can bring about change.

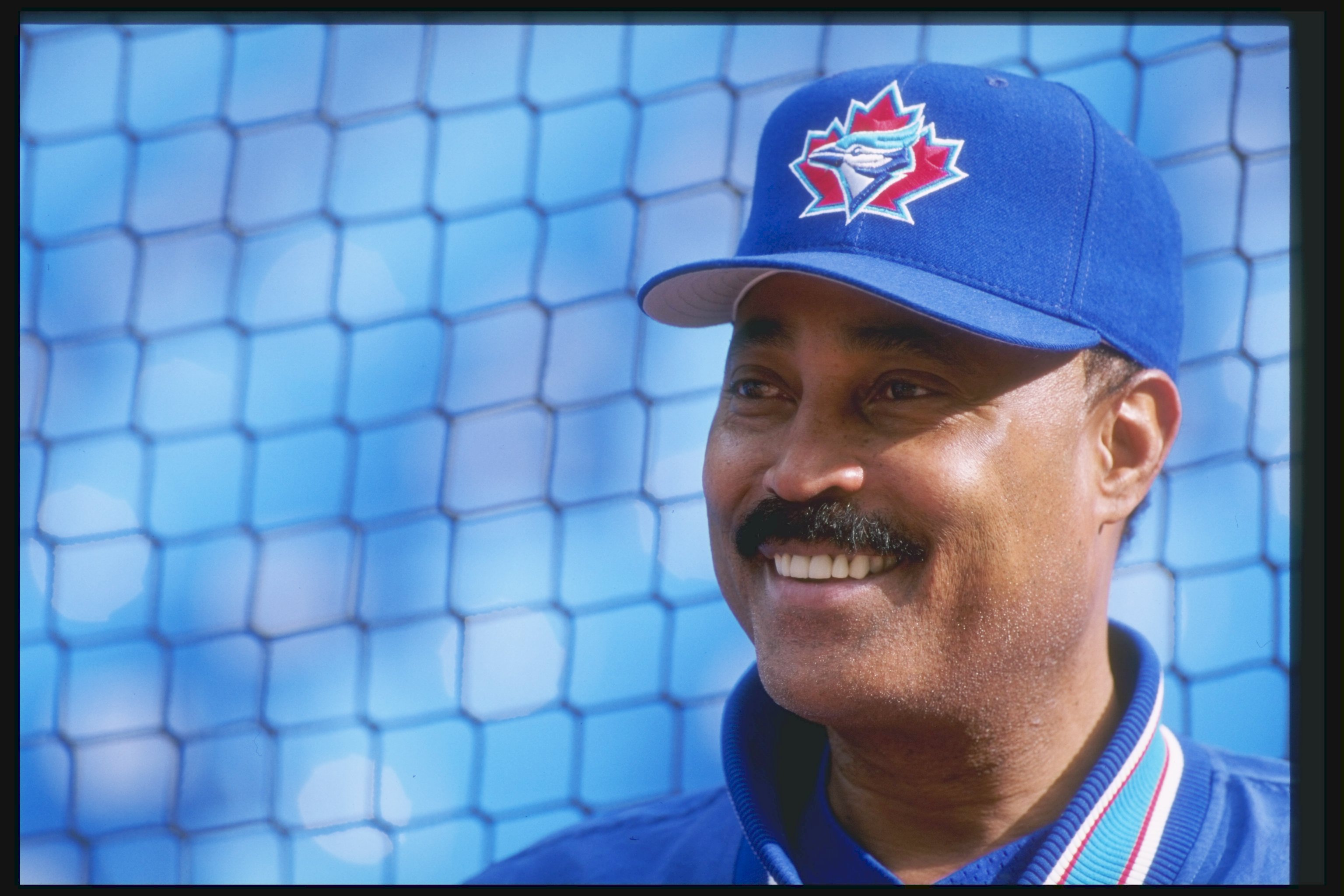

The former manager of the Toronto Blue Jays, Cito Gaston,

Cito Gaston won two World Series titles and went 894-837 in two stints as the Toronto Blue Jays’ manager.

Gaston may be Exhibit A that perhaps even a superstar black baseball manager may not be a catalyst to compel change.

When Gaston took over as manager of the Blue Jays in 1989, the team was 12-24. They ended up winning the division.

Gaston managed the Blue Jays to four division titles. In 1992, he became the first black manager in MLB history to win a World Series title. He followed that up by leading Toronto to a second consecutive World Series win in 1993.

On Thursday afternoon, during a phone discussion, Gaston told me “I’m still not considered to have even a chance to go into the Hall of Fame.” They think I didn’t win enough games. Of course, I didn’t have any work for 10 years, either.

In 1997, Gaston was sacked after four consecutive losing seasons. Unlike other World Series-winning managers who are promptly recycled, Gaston did not earn another managerial position until 2008, when he was rehired by Toronto.

At one point, “I stopped going to interviews at one time because they interviewed me simply because they had to interview a minority candidate,” said Gaston, who went 894-837 in 12 seasons of managing the Blue Jays.

If winning is not enough, then what’s the difference between having great black players opening the door for other players, as Robinson did, and successful black coaches opening the door for other coaches? “I don’t know, it should go without saying that they should be given a chance,” Gaston added.

Gaston stated he thought I was being stupid if I assumed winning black managers would have the same impact as winning black players.

“I suppose you are, because it didn’t alter that much for me,” he said. “You would expect that winning would assist them to see that blacks are qualified to manage baseball teams.” But I don’t know that. You see, where we are now? “

He added: “I don’t think it counts that much until the owners state that a black man can do as good a job as anyone else. Until that changes, it’s not going to change. I know the way things should go, but it’s not going that way at all. “

Despite the glacial pace of change in and out of baseball, Gaston still said he was optimistic for the future and ever grateful to Robinson for all he endured. It makes the slights Gaston experienced appear insignificant.

“He didn’t sacrifice all of that for nothing,” Gaston remarked.

Perhaps I was being naive to expect that success would bring about the same seismic changes for black coaches as it has for black athletes. It will take more than a victorious black manager or coach to obliterate the color barrier in white-controlled sports.

Yet on a day that we celebrate Robinson, we celebrate endurance more than anything. That’s what helps bring about change.

In some ways, that is a win.

“We just have to keep pushing,” Gaston added. “Everything moves slowly.”

William C. Rhoden, the former award-winning sports columnist for The New York Times and author of Forty Million Dollar Slaves, is a writer-at-large at Andscape.