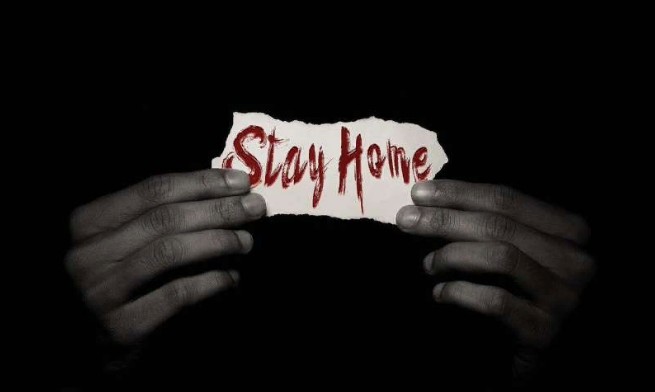

Women in impoverished countries had serious mental health implications as a result of pandemic lockdowns

Study: Lockdowns may be necessary to stop the spread of COVID-19, but they are linked to higher rates of sadness and anxiety as well as food scarcity. This is true for women living in India and other countries with limited resources.

According to a study from the University of California, San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy, women whose social status may make them more vulnerable—those with daughters and those living in female-headed households—experienced significantly more mental health losses as a result of lockdowns than those without.

The study, which will be published in a future issue of the Journal of Economic Development, surveyed 1,545 households in rural areas across Northern India over the phone.

The polls were conducted in the fall of 2019, before the pandemic, and in August of 2020, towards the peak of India’s first COVID-19 wave.

They could compare the health of women who had lockdowns for a few months to those who didn’t have lockdowns. Because some towns and districts had different containment practices, the researchers were able to do this.

Scientists looked at a lot of different things when they did their analysis, like how many times COVID was used, how many people were hospitalized, and how many people died because of the new coronavirus.

Moving from zero to average lockdowns is associated with a 38% increase in sadness, a 44% increase in anxiety, and a 73% increase in weariness among women polled.

“In developing countries, not having access to jobs and socialization outside the home can be quite deleterious to women’s mental health,” research co-author Gaurav Khanna, an assistant professor of economics at the School of Global Policy and Strategy, said.

Women suffered significant economic losses as a result of the pandemic. In the study, around a quarter of the households said they ate fewer meals than they would in a typical month. In many developing countries, women’s food intake is the first to be cut back when there is not enough food to go around.

“We wanted to discover how lockdown policies affect women in lower-income nations with fewer social safety nets to withstand these shocks,” Khanna explained.

“The implications of lockdown measures are magnified for women, according to our research. We hope that politicians in developing nations and abroad understand the ramifications of these practices, particularly for those in vulnerable positions, because communities could suffer similar lockdowns if there is another wave.

The study offers policy ideas that could assist women cope with the mental and physical health implications of the pandemic.

As the authors say, “Policymakers should think about what supportive measures are needed to keep lockdowns from causing economic devastation.” They should focus aid, such as food, on the most vulnerable households and women.

For example, the government delivered food to rural regions in some parts of India, which helped to avoid malnutrition and food insecurity.

Over-the-phone counseling and helpline services can also help with the pandemic’s mental health effects, according to the authors.

While the findings are aimed at countries that aren’t as well-off, they have consequences for women around the world who are locked down.

“We believe the impact on women and mothers in particular was exacerbated in the United States,” Khanna said. Because of conventional gender roles in child care, when children are not in school or daycare, the burden largely falls on women. Women will be impacted differently by these regulations, and policymakers should be aware of this. “