Humans can withstand lower maximum temperatures and humidity than previously believed.

As global temperatures rise as a result of climate change, researchers are becoming more interested in the maximum environmental conditions to which people can adapt, such as heat and humidity. According to new Penn State research, the temperature in humid climates may be lower than previously thought.

It was previously thought that a wet-bulb temperature of 35 degrees Celsius (equivalent to 95°F at 100% humidity or 115°F at 50% humidity) was the maximum a human could tolerate before losing control of their body temperature, potentially resulting in heatstroke or death if exposed for an extended period of time.

A thermometer with a wet wick over its bulb is used to measure wet-bulb temperature, which is impacted by humidity and air movement. It denotes a humid temperature in which the air is saturated and holds as much moisture as it can in the form of water vapor; at that skin temperature, a person’s perspiration will not evaporate.

However, the researchers discovered that even for young, healthy people, the real maximum wet-bulb temperature is lower—around 31 degrees Celsius wet-bulb or 87 degrees Fahrenheit at 100% humidity—in their latest study. The temperature is likely to be significantly lower for older people, who are more susceptible to heat.

The findings could help individuals better plan for extreme heat events, which are becoming more common as the world warms, according to W. Larry Kenney, professor of physiology and kinesiology and Marie Underhill Noll Chair in Human Performance.

“We can better prepare people—especially those who are more vulnerable—ahead of a heat wave if we know what those upper temperature and humidity limitations are,” Kenney said. “This could include prioritizing the sickest people who require care, setting up notifications to go out to a community when a heatwave is approaching, or creating a chart that provides information for various temperature and humidity ranges.”

It’s also worth noting that utilizing this temperature to estimate risk only makes sense in humid areas, according to Kenney. Sweat is able to drain off the skin in drier regions, which helps to reduce the body temperature. The temperature and ability to sweat, rather than the humidity, are more important in unsafe dry heat situations.

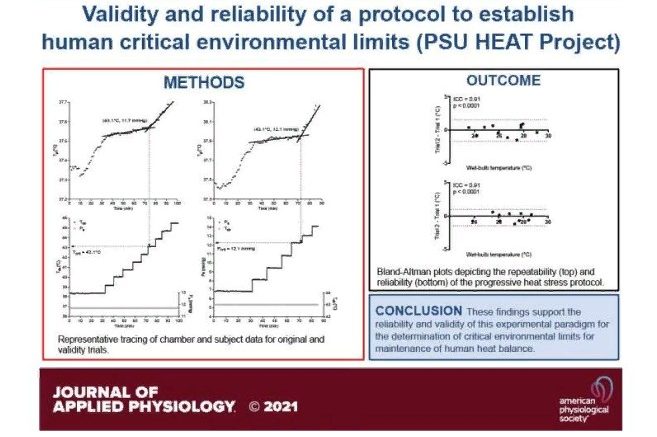

The research was published in the Journal of Applied Physiology recently.

Previous studies had assumed that a wet-bulb temperature of 35 degrees Celsius was the upper limit of human adaptation, but that temperature was based on theory and modeling rather than real-world evidence from humans, according to the researchers.

Kenney and his colleagues intended to test this theoretical temperature as part of the PSU H.E.A.T. (Human Environmental Age Thresholds) project, which is looking at how hot and humid an environment has to be before older persons have trouble managing heat stress.

“When you look at heat wave statistics, you’ll notice that the majority of people that die during heat waves are older people,” Kenney said. “Heat waves will become more common—and more severe—as the climate changes. As the population ages, there will be an increase in the number of older persons. As a result, studying the intersection of those two movements is critical.”

The researchers gathered 24 volunteers between the ages of 18 and 34 for their study. While the researchers intend to do these tests on older folks as well, they preferred to start with children.

“Young, fit, healthy people tend to endure heat better,” Kenney explained, “so they will have a temperature limit that can serve as a ‘best case’ baseline.” “Older people, people on drugs, and other susceptible populations will very certainly have a lower tolerance limit.”

Each subject swallowed a tiny radio telemetry device wrapped in a capsule prior to the experiment, which would then detect their core temperature throughout.

The individual was then placed in a dedicated environmental chamber with temperature and humidity controls. While the subject engaged in light physical activity such as light cycling or walking slowly on a treadmill, the temperature and humidity in the chamber gradually increased until the person’s body could no longer sustain its core temperature.

The researchers discovered that crucial wet-bulb temperatures varied from 25 to 28 degrees Celsius in hot-dry conditions and from 30 to 31 degrees Celsius in warm-humid environments, all of which were lower than 35 degrees Celsius wet-bulb temperatures.

“Our findings imply that when it gets above 31 degrees wet-bulb temperature in humid places of the world, we should start to be concerned—even about young, healthy people,” Kenney said. “As we continue our research, we’ll look at what that number is in older folks, because it’s likely to be considerably lower.”

Furthermore, because individuals adapt to heat differently depending on humidity levels, the researchers concluded that there is unlikely to be a single cutoff limit that can be designated as the “maximum” that humans can tolerate across all settings found on Earth.